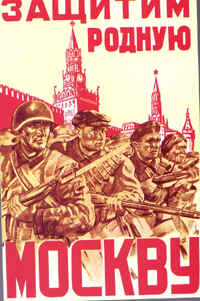

The Battle for Moscow – the Germans code-named it ‘Operation Typhoon’ – started on October 2nd 1941. The capture of Moscow, Russia’s capital, was seen as vital to the success of ‘Operation Barbarossa‘. Hitler believed that once the heart – Moscow – had been cut out of Russia, the whole nation would collapse.

|

The initial stages of Barbarossa have been seen as massively successful for the Germans and catastrophic for the Russians. Few would deny the success of the German attack – 28 Russian divisions were put out of action in just three weeks and more than 70 divisions lost 50% or more of their men and equipment. Blitzkrieg had ploughed through the Red Army. Hitler’s belief that the Red Army would crumble seemed to be coming true. However, the Germans had also suffered in their attacks on Russia. By one month into Barbarossa, the Germans had lost over 100,000 men, 50% of their tanks and over 1,200 planes. With its army split between east and west Europe, these were heavy casualty figures. Hitler’s belief that the Red Army would be crushed also meant that there had been little consideration of the Russian winter and very many of the Wehrmacht in Russia had not been equipped with proper winter clothing. The battle that raged around Smolensk had critically held up the advance of the Germans.

Ironically for an army that was to suffer from the Russian winter, ‘Operation Typhoon’ started off in ideal weather conditions on October 2nd, 1941. Field Marshall von Bock had been given overall command of the attack on Moscow. Hitler had ordered that units in other parts of the Russian campaign be moved to Moscow – General Hoepner’s IV Panzer group had been moved from Leningrad – hence why the Germans did not have sufficient men to launch an attack on the city and why it had to be besieged. For the attack, Bock had at his disposal 1 million men, 1,700 tanks, 19,500 artillery guns and 950 combat aircraft – 50% of all the German men in Russia, 75% of all the tanks and 33% of all the planes. To defend Moscow, the Russians had under 500,000 men, less than 900 tanks and just over 300 combat planes.

Hitler had made it clear to his generals what he wanted from them. Chief-of-Staff Halder wrote in his diary:

| “It is the Führer’s unshakable decision to raze Moscow and Leningrad to the ground, so as to be completely relieved of the population of these cities, which we would otherwise have to feed through the winter. The task of destroying the cities is to be carried out by aircraft.” |

On October 12th, ten days into the attack by Bock’s Army Group Centre, he received a further order from German Supreme Command:

| “The Führer has reaffirmed his decision that the surrender of Moscow will not be accepted, even if it is offered by the enemy.” |

The order went on to instruct Bock that gaps could be left open for people in Moscow to escape into the interior of Russia where administrating them would cause chaos.

The attack started well for the Germans. The Russians found it difficult to communicate with all parts of their defences and infantry divisions frequently had to face tanks without air or artillery support. By October 7th, even Marshall Zhukov was forced to admit that all the major roads to Moscow were open to the Germans. Large parts of the Red Army had been encircled at Vyazma (the 19th, 24th, 29th, 30th, 32nd and 43rd armies) and at two places near Bryansk (the 3rd, 13th and 50th armies) such was the ferocity of the German attack and the state of the Russian army then.

Ironically, it was these armies that had been trapped near Vyazma and Bryansk that caused the Germans their first major problem in the attack on Moscow. The Germans could not simply leave nine Russian armies in their rear as they advanced east. They had to take on these trapped armies. By doing so, they slowed down their advance to Moscow to such an extent that the Red Army was given sufficient breathing space to reorganise itself and its defences under the command of Marshall Georgy Zhukov – the man who ‘never lost a battle’. The choice of Zhukov was an enlightened one:

| “In my view, Zhukov remains always a man of strong will and decisiveness, clear and gifted, exacting, persistent and purposeful. These qualities are all, undoubtedly, indispensable to a great military leader, and Zhukov has them.”Marshall of the Soviet Union Rokossovsky |

Zhukov organised his defence along the so-called ‘Mozhaysk Line’. The Germans attacked this line on October 10th – by which time they had dealt with the Russians at Vyazma. Though on paper the delay to the Germans had been mere days, to the Russians it allowed them time to move their forces to where Zhukov believed they would be needed. Even so, the Germans broke through the Mozhaysk Line at a number of places and for all of Zhokov’s work, Moscow was still very much threatened. Parts of the German army got to 45 miles of Moscow’s centre before the tide was turned and a stalemate developed with little movement on either side.

On November 13th, senior German commanders met at Orsha. It was at this meeting that the decision was taken to start a second assault on Moscow. During the stalemate, the Russians had sent 100,000 more men to defend Moscow with an extra 300 tanks and 2,000 artillery guns.

Moscow itself had been turned into a fortress with 422 miles of anti-tank ditches being dug, 812 miles of barbed wire entanglements and some 30,000 firing points. Resistance groups had also been organised to fight both in the city, should the Germans enter Moscow and in the area around the city. In all, about 10,000 people from Moscow were involved in planned resistance activities. Lieutenant-General P A Artemyev was given the task of defending the city. Between 100 and 120 trains provided the city with what was required on a daily basis at a time when the Germans could only average 23 trains a day when they required 70 – such was the effectiveness of partisan activity.

The second assault narrowed its target area so that as much fire power could be concentrated in one area as possible. The belief that was held was that if one small part of the city was entered, all the defences surrounding it would fall once the might of the Panzer units fanned out. However, the attack met with fierce Russian resistance. The Germans got as far forward as 18 miles from Moscow’s centre (the village of Krasnaya Polyana) but the Russian defence line held out. It is said that German reconnaissance units actually got into the outskirts of the city but by the end of November the whole forward momentum of the Germans had stalled. By December, the Russians had started to counter-attack the Germans. In just 20 days of the second offensive, the Germans lost 155,000 men (killed, wounded or a victim of frostbite), about 800 tanks and 300 artillery guns. Whereas the Germans had few men in reserve, the Russians had 58 infantry and cavalry divisions in reserve. STAVKA proposed to use a number of these divivions to start a counter-offensive against the Germans – Stalin himself made it clear to Zhukov that he expected a counter-attack to start on December 5th in the battle zone to the north of Moscow and on December 6th in the battle zone to the south of the city. The attacks took place at the times decreed by Stalin and they proved highly effective against an enemy that was being hit hard by sub-zero winter temperatures – night temperatures of -20F were not uncomon.

The impact of these attacks so unnerved Hitler that he issued the following order:

| “The troops must be compelled by the personal influences of their commanders, commanding officers, and officers, to resist fanatically on their present positions, without regard to enemy breakthroughs on the flanks and in the rear. Only by leading their troops in this way can the necessary time be gained for movement of reinforcements from the homeland and the West which I have ordered to be carried out.”Hitler |

However, his call was in vain. The Wehrmacht was pushed back between 60 and 155 miles in places and by January 1942, the threat to Moscow had passed. Hitler’s response to this was to move 800,000 men from the west of Europe to the Eastern Front – thus ending forever any chance, however very small it may have been, of ‘Operation Sealion‘ being carried out. He also dismissed 35 senior officers as well – including the Commander-in-Chief of the Army, Brauchitsch, and the three army commanders in the field – Bock, Leeb and Rundstedt.

Related Posts

- The Battle for Moscow - the Germans code-named it 'Operation Typhoon' - started on October 2nd 1941. The capture of Moscow, Russia's capital, was seen…

- The Battle of Kursk took place in July 1943. Kursk was to be the biggest tank battle of World War Two and the battle resulted…

- The Battle of Kursk took place in July 1943. Kursk was to be the biggest tank battle of World War Two and the battle resulted…