The Battle of Ypres (and the numerous battles that surrounded this Flanders town) has become linked forever with World War One. Along with the Battle of the Somme, the battles at Ypres and Passchendaele have gone down in history The town had been the centre of battles before due to its strategic position, but the sheer devastation of the town and the surrounding countryside seems to perfectly summarise the futility of battles fought in World War One.

The land surrounding Ypres to the north is flat and canals and rivers link it to the coast. The major centre in this part of Flanders was Ypres. Control of the town gave control of the surrounding countryside and all the major roads converged on the town. To the south of the town the land rises to about 500 feet (the Mesen Ridge) which would give a significant height advantage to whichever side controlled this ridge of high land.

British troops entered Ypres in October 1914. They were unaware of the size of the German force advancing on the town. However, numbers did not make up for experience as the Germans used what were effectively students to attack professional British soldiers based north of the town at a place named Langemark. Eyewitnesses claim to have seen the German troops, with just 6 weeks training, with arms linked singing patriotic songs as they advanced towards the British. 1,500 Germans were killed and 600 taken prisoner.

Fierce fighting took place around the town and neither the British nor the Germans could claim to control the area. At a place called Wijtschate (about 10 miles south of Ypres) a German corporal called Adolf Hitler rescued a wounded comrade and won the highest honour a German soldier could win – the Iron Cross. Despite fearsome losses on both sides, neither could dominate the other.

British soldiers huddle in the snow just outside of Ypres – in the top left hand corner. The treeless background summarises the bombardment the region suffered from and the conditions the soldiers lived in.

The first days of November directly affected the town. Each day Ypres was shelled and civilian casualties were high. This tactic set the scene for what Ypres was to suffer for several more years. By the winter, the Germans had not taken Ypres and heavy rain meant that any movement was impossible as the roads turned to mud. The first battle at Ypres limped to a halt.

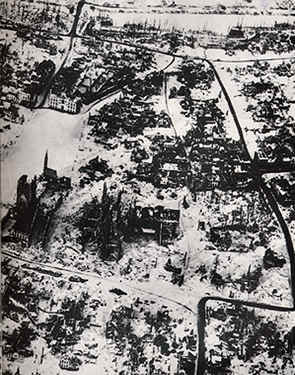

The devastation of Ypres – barely a building was left undamaged by shell bombardment

Once the weather had settled, the Germans prepared for a new attack. They used deadly chlorine gas against defending French troops. Having never experienced this before, terrified French soldiers fled. Gas had worked as it had got them to leave their positions. The situation was saved by Canadian troops who used handkerchiefs soaked in urine as gas masks and launched a counter-attack on the Germans. It was successful and the Germans lost the gains they had made.

Also in April, the French exploded mines under the German position held at Hill 60 – in fact, a mound created from the rubbish cleared when a railway cutting was made. Whoever controlled Hill 60 had a perfect view of what was going into Ypres and what was leaving. Hence its strategic value. Though successful, the area was reduced to a muddy bog. The British took Hill 60 but were pushed out by another successful poison gas attack by the Germans. The Germans were only pushed out of Hill 60 in 1918.

To the south of Ypres lies Mesen. The hills around Mesen had been controlled by the Germans since 1914, and to give the Allies a morale boost, the Allied High Command ordered an attack on Mesen Ridge. The Allies had spent time digging tunnels underneath the Ridge which were packed with explosives. On June 7th,1917, nineteen of the mines were detonated. The noise of the explosions was heard in London. The stunned German troops on the Ridge were easily taken by the Australian and New Zealand troops that attack the Ridge after the explosions.

To the north east of Ypres, plans went less well for the Allies. If one battle summarises the pain of war it was Passchendaele. In October 1917 the area was drenched with rain – for a month.

Conditions for the troops were appalling. Trench foot was common on both sides The fight for Passchendaele and the extra height the area would give the victors started on October 12th. By November 6th, the area had been captured for the Allies at terrible loss for both sides – for about 900 metres of land.

The arrival of the Americans into the war in 1917, hastened the defeat of the Germans and the last shell fell on Ypres on the 14th of October 1918.

In the area around Ypres – including Hill 60, Passchendaele, Lys, Sanctuary Wood etc. – over 1,700,000 soldiers on both sides were killed or wounded and an uncounted number of civilians.