|

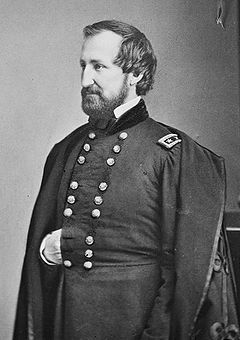

William Rosecrans was a senior Union general during the American Civil War who played a major part in the so-called Western Theatre of the war.

Rosecrans was born on September 6th 1819 in Delaware County, Ohio. His father ran a tavern and worked a farm. He had little education in his early years and left home at the age of thirteen to work as a store clerk. Rosecrans could not afford to go to college but in 1838 he tried to get a place at the US Military Academy at West Point. His application was successful and for the first time Rosecrans experienced formal education. He excelled in such an environment and in 1842 he graduated fifth out of fifty-two cadets in his class.

He left West Point with the rank of second lieutenant and joined the Corps of Engineers. The Corps was a highly respected unit and it was a sign of just how far Rosecrans had moved that a boy brought up on a farm with little education could have joined such a prestigious military unit.

After a year building sea walls, he returned to West Point as a lecturer in engineering. He left the army in 1854 as a result of health issues and took over a mining concern in modern day West Virginia. Rosecrans became president of the Preston Coal Oil Company and made a name for himself in business. Rosecrans continually experimented with new inventions and while working on one of these – ironically a safety oil lamp – he was severely burned. By the time he had recovered from his burns, the American Civil War had started.

Rosecrans re-joined the Union Army and became aide-de-camp to General George McClellan with the rank of colonel. On May 16th 1861, Rosecrans was promoted to Brigadier General and he was successful at the battles fought at Rich Mountain and Corrick’s Ford. After the defeat of the Union army at the First Battle of Bull Run, McClellan handed over to Rosecran’s the command of what was to become the Department of Western Virginia. However, the rest of 1861 was an anti-climax from Rosecran’s point of view as nearly all of his men were transferred to another command and with just 2,000 men remaining, Rosecrans was not capable of doing what he wanted to do – attack Winchester in Virginia. Rosecran’s believed that the fall of Winchester would be a major blow to the Confederacy but his planned attack never materialised. In fact, his remaining 2,000 men were transferred to another department, the Mountain Department, and Rosecran’s went to work in Washington DC. While in the capital, Rosecrans came into contact with Edwin Stanton, Secretary of State for War. Neither hit it off with the other and Stanton became one of Rosecran’s biggest critics.

However, he moved away from Washington in May 1862 to the Western Theatre when he was given the command of two divisions in Major General Pope’s Army of the Mississippi. Rosecran’s fought at Corinth and the Battle of Iuka. While his performance at both did not win the full approval of General Ulysses Grant, the Union media gave Rosecran’s positive write-ups and portrayed him as a Union hero. The result of this was that Rosecrans was given the command of what was to become the Army of the Cumberland with the rank of Major General. While Grant was keen to see Rosecrans leave his overall command, he was not happy that a senior officer was being given credit for what Grant perceived to be a lack of aggression on the battlefield. At both Corinth and Iuka, Grant had ordered Rosecran’s men to pursue withdrawing Confederate forces, but on both occasions Rosecran’s decided to let his exhausted men rest before starting any chase. By the time they had recovered, any pursuit was of little value.

To his detractors, Rosecrans showed a similar lack of urgency as head of his army. Rather than actively pursue the enemy, Rosecrans put his effort into training his men so that they were fully combat ready. In late December 1862, Rosecran’s gauged that his men were ready and he actively pursued Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee. They fought at the Battle of Stones River on December 31st. It was a very bloody battle that lasted until January 2nd and ended with a Union victory that gave them control of Middle Tennessee. President Abraham Lincoln wrote to Rosecran’s to personally congratulate him and thank him for the victory that was a major boost to the North’s morale. It was after this battle that Rosecran’s army was formally titled the ‘Army of the Cumberland’.

The winter of 1862/63 was very bad where the Army of the Cumberland was based. It was for that reason that Rosecran’s stayed where he was and refused to pursue the defeated army of Braxton Bragg. This incurred the anger of Lincoln who wrote to Rosecran’s imploring him to pursue and attack Bragg. Rosecran’s wrote back that the risks of moving out of his winter quarters far exceeded any benefits that might be gained. Rosecrans also argued – and continued to argue his case – that having the Army of the Cumberland based in Middle Tennessee meant that the Confederate Army was forced to cover him and that Bragg dare not move his men elsewhere (such as helping out against Grant) as it would leave Rosecran’s with a free hand in the region. It was not an argument that was backed by Lincoln. Rosecrans responded by asking his senior generals if they agreed with what he was doing and the vast bulk did – 15 out of 17 generals. It was only on June 24th 1863 that Rosecrans moved out against Bragg – once he felt that his men were up to the task.

The attack on Bragg went exceptionally well. Lincoln wrote that it was “the most splendid piece of strategy”. Bragg was pushed back to Chattanooga. Rosecrans continued to march on Bragg and his pursuit culminated in the Battle of Chickamauga (September 1863). Here a misunderstanding of a command proved to be a disaster for Rosecrans. Two division commanders were ordered to close up their men to present a concentrated unit for the battle. Somehow they interpreted Rosecran’s command as to split up their men. By sheer coincidence it was at this point that Bragg planned a major attack against an enemy that was in the process of greatly weakening itself as a fighting unit. The Confederates under Bragg tore a large hole into the Army of the Cumberland and it fell back to Chattanooga in disarray. The defeat would have been a disaster but for the bravery of Major General George H Thomas who organised a brave defence on Horseshoe Ridge that delayed Bragg’s advance. It was the Union’s worst defeat in the Western Theatre and spelled the end of Rosecrans’s career, as he never recovered his prestige after Chickamauga. Rosecrans and his men were besieged in Chattanooga and it took 15,000 men commanded by General Joseph Hooker, supported by 20,000 men from William Sherman’s army, to relieve the city. Grant had already made up his mind to relieve Rosecrans of his command.

Chickamauga was the last major part Rosecrans played in the American Civil War. During 1864, he fought in Missouri against the raiders there who plagued the state. There was an attempt to get him into politics but it came to nothing.

Rosecrans left the volunteer army on January 15th 1866 and he resigned from the regular army on March 28th 1867. He went into business and politics, serving as a House member for California and as Register of the Treasury (1885 to 1893).

William Rosecrans died on March 11th 1898.

Related Posts

- The Battle of Chickamauga was fought between September 19th and September 20th1863. Chickamauga was a major victory for the army of the Confederate general Braxton…